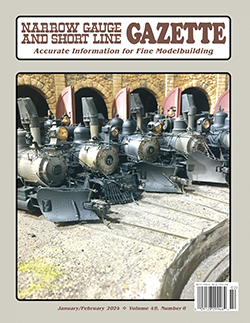

Gold! Gold! Gold! Those words were the driving force behind the mad rush to the Klondike in 1896 and 1897. Yet, by 1898 the fever was waning in the Yu-kon, and word of other gold-rich regions echoed in the dance halls, saloons, and along the trails. In the spring of 1898, Fritz Miller and Kenneth MacLaren left the trail north at Bennett, B.C., and headed east. They crossed the frozen Taku Arm of Tagish Lake and then Lake Atlin.

The two men discovered gold on Pine Creek in the Atlin District. They needed supplies for an extended stay, and when they returned with supplies they were followed. Shortly afterwards close to 3,000 people rushed the area; all of them looking to strike it rich. When word of this gold find reached the construction camps of the White Pass & Yukon Route, many of the workers left for Atlin, taking the company’s pickaxes and shovels with them.

The name Atlin is derived from a Tlingit phrase meaning “big body of water.” Lake Atlin is the largest naturally occurring lake in British Columbia. The Atlin District was the richest gold mining area in British Columbia. The largest nugget found in the Atlin District weighed 48 ounces or about four pounds! The Pine Creek valley is a wide valley stretching east from Lake Atlin twenty-five miles. Surrounded by mountains, the Atlin District would be known as the “Switzerland of the North.”

ABOVE: A great view of the Duchess next to a large stockpile of firewood. The lack of the front driver connecting rod can be seen clearly. The front drivers were disconnected about 1900 when the locomotive was converted from 30-inch gauge to 36-inch gauge. —Bruce Prior collection

In February 1899, a charter was issued by the British Columbia legislature to build a tramway or railway across the isthmus from Taku Arm on the east side of Tagish Lake to Scotia Bay on the west side of Lake Atlin. This charter gave powers to construct telegraph lines, to utilize the Atlin River for electric power purposes, and to build wharves and facilities for steamboats. The new company was named the Atlin Short Line Railway & Navigation Company (ASL) and opened a tramway using horses for power on June 6, 1899. The 2¼-mile-long tramway had wharves at each end for loading and unloading steamboats.

By the end of 1899, the population of the Atlin District was about 5,000 people. Temporary control of the ASL passed to the John Irving Navigation Co. in the summer of 1899. Irving lost control of the line and he started planning a second tramway, but by May 1900 he had regained control of the ASL. The White Pass & Yukon Route bought the assets of the John Irving Navigation in June 1900 including the steamboats, the tram, the wharves, and a recently purchased used locomotive called the Duchess.

ABOVE: The Duchess on a siding at Scotia Bay prior to the 1917 rebuilding. If this was really taken at Scotia Bay, then the Taku Tram had two switches and sidings. Scotia Bay was the eastern terminus of the Taku Tram, (also known as the Atlin Short Line).

—Photo by LHP, courtesy the Skagway Museum, Dedman Collection-0151

The story of the Duchess starts with Robert Dunsmuir who came to Vancouver Island, B.C., in 1851 from Hurlford, Scotland, as an indentured worker of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The company was looking to exploit the coal resources on Vancouver Island. After his indenture was over, he continued working for Hudson’s Bay until he discovered his own outcropping of coal while fishing Diver Lake in 1869. Dunsmuir, Diggle & Co. was formed and was producing 50,000 tons of coal per year by 1875. They ordered two 30-inch gauge 0-6-0 saddle tank locomotives from Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1878, number 1 the Duke, and number 2 the Duchess. The locomotives had 31-inch diameter boilers, 10- x 12-inch cylinders, and 28-inch diameter drivers. The other investors were soon bought out and the company was renamed Dunsmuir & Sons in 1883. Robert Dunsmuir died in 1889 and 4 years later, the Duchess was owned by the Wellington Colliery, also part of the company.

In 1899, the Duchess’ gauge was widened to 36 in., and in doing so the front drivers were disconnected, making the engine a 2-4-0 or a 0-(2)4-0. It is unclear whether the Wellington Colliery did this, or if it happened when the locomotive was sold later that same year to Albion Iron Works. An inspec-tion today reveals the reason the front rods were removed; there was no room for the rod bolts when the gauge was widened. A curious note is that James Dunsmuir, (Robert Dunsmuir’s son) was the president of the Albion Iron Works at the time. The Duchess was sold about April 1900 to the John Irving Navigation Co. for use on the Atlin Short Line…