by Ben Popper/photos by the author

by Ben Popper/photos by the author

In birding there is what is called the “spark bird.” The species that triggers a lifelong passion for birding. It’s the one bird that gets people hooked on seeing, cataloging, photographing, collecting, painting, and traveling to be in the world of birds. I would wager that a lot of us can point to something similar that got us into model railroading.

In the spring of 2020 at a train show in Monroe, Wash., Al Jones of the Moose Creek On30 Logging Railroad introduced my 12-year-old son and I to the wonderful world of narrow gauge modeling. Our plan to wander the show looking at all the different layouts evaporated when he handed us a cab control creating my “spark bird” for narrow gauge and logging railroads. Our day at the show turned into a day running trains on what became our new club layout.

At that moment, I didn’t realize what I was in for or that the world of narrow gauge modeling is so vast; I had only stumbled upon the scene. Like a rotary plow on a mountain pass, I couldn’t get my mind off of it. The combination of narrow gauge logging railroads’ ingenuity and Pacific Northwest rail history collided with my unbridled creativity. I was not prepared for how deep I was about to dive into this “hobby.”

Al said on that first day that one of the fun things about a freelanced narrow gauge logging railroad is that if we can imagine it, it probably existed. He didn’t know how much I was going to take that statement to heart. Over the following months as I poured over volumes of text and pictures covering logging railroads, and practices all over the west coast, I started making note of models I wanted to build. While my historical education flourished, I also started learning the physical parts of modeling: standards, building, painting, modifying. I’d jump at the opportunity to build a unique looking kit, realizing that readily available options for On30 are limited. Soon, not satisfied with the level of detailing that would be provided in a kit, I was supplementing the build with piquant parts to make things look a little more like they may have in real life.

Building The Model

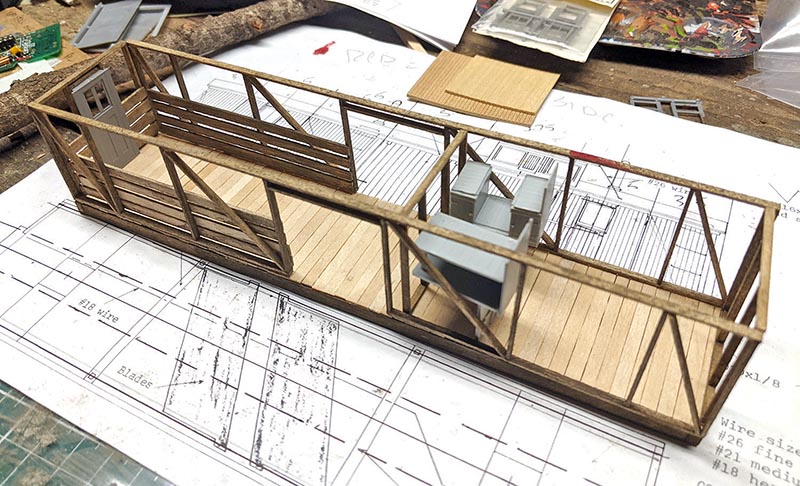

And that is when I was about to make a significant leap. I found an old Ambroid O scale Lehigh & Hudson River Flanger Caboose kit. Out of the box, the kit posed all sorts of issues. The car itself is too wide and long for narrow gauge. It also represents a piece of maintenance of way equipment native to the east coast, far from the home of our Pacific Northwest layout. But, with Al’s words about if you can imagine it, a logging railroad would build it, I did some mental gymnastics and decided I could use the plans and narrow the car, pretending that it was shop built and used for limited service. I’d already seen photos of long, drover style cabooses with cupolas on the McCloud River Railroad and Schafer Brothers Logging Co. There is nothing to say the shop crew couldn’t put a pair of flanger blades on the bottom of any of those cars.

I quickly figured out that there wasn’t much from the original Ambroid kit I was going to be able to use. So, I was committing to scratchbuilding a significant part of the model, something I hadn’t tried before. Scratchbuilding would allow me to make creative choices the kit wouldn’t have given me. Most significantly, this would be my first attempt at building a car with an interior. Using the Ambroid plans as a guide, I framed all the walls, built, and decked the car’s frame and stained, painted, and cut the siding. The cupola end uses about 14 feet of the car’s length leaving 20 feet for the equipment end and flanger mechanism. I prepped, modified, and assembled a pair of Grandt Line passenger trucks along with the caboose interior and doors.

I love snow removal equipment and the flanger part of this car was why I was building it. Because I was modeling this car in narrow gauge, the blades were too big both in height and width, so I needed to build my own. Fortunately, the Phillipsburg Railroad Historians in New Jersey are restoring this car, and their internet postings provided some much-needed pictures of the flanger to work off of as a reference. It took me a few tries to build the blades. The first two attempts did not come out looking realistic because I was trying to shortcut using found materials. After I shifted to scratchbuilding the entire assembly out of styrene, I found the control it gave me of every individual piece allowed me to build them with more detail than I thought I could. The result changed my game…