The story of the White Pass & Yukon Route (WP&YR) is one of steep grades, incredible scenery, bitter cold, and a stubborn gold miner’s attitude. The railway started with the gold lust of the Klondike Gold Rush of the mid-1890s and a need to get people and supplies to the far north. The 110 miles from the Alaskan boom town of Skagway, north to the town of Whitehorse in the Yukon Territory (YT), was completed in two years, two-months, and two days. This feat was accomplished with British financial backing, Canadian engineering, and mostly American labor. The locomotives of the White Pass & Yukon were an interesting assortment from the beginning. In this series I will explore the early locomotives of this unique and fabled railroad, accompanied by beautiful drawings from long-time GAZETTE contributor, David Fletcher. I start with the first locomotives in the Alaska Territory, WP&YR numbers 1 and 2.

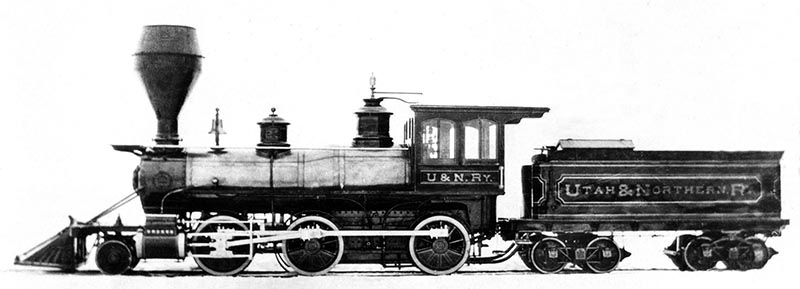

ABOVE: Utah & Northern #23 as-built by the Brooks Locomotive Works in 1881, inclusive of the original Pennsylvania Railroad inspired livery, dating to 1868, which had become popular with a number of locomotive firms by 1880. Number 23 would go on to become the WP&YR 1 in 1898, and last on that line until retirement in 1941. —David Fletcher Collection

The first locomotives to arrive in the Alaska Territory were built in 1881 by the Brooks Locomotive Works of Dunkirk, N.Y., for the Utah & Northern Railway (U&N) as their numbers 23 and 37. Both were 2-6-0s with 42-inch diameter drivers, and 14×18 inch cylinders. The U&N was a narrow gauge railway spur off of the Union Pacific section of the transcontinental railroad at Ogden, Utah. Originally, the Utah Northern Railway (1871–1878), foreclosure led to its sale to Jay Gould and the Union Pacific who changed the name to the Utah & Northern Railroad. Capital was poured into the line and by the end of 1881 the railroad had been extended all the way to Butte, Mont., nearly 600 miles from Ogden. It was during this infusion of money that the 2-6-0s were ordered from Brooks. The locomotives were renumbered in 1885 to the UP’s numbering system, 23 became 80 and 37 became 94. But their usefulness on the line was short-lived as the railroad was widened to standard gauge in July 1887. Both were sold in November 1889 to the Columbia & Puget Sound Railroad.

The Columbia & Puget Sound Railroad (C&PS) began as the 3-foot gauge Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad & Transportation Co. (S&WW) in 1873. The Oregon Improvement Company (OIC) bought the S&WW in 1880 and renamed it the C&PS. The OIC was a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific and improvements to the line were facilitated during the mid- and late-1880s. This is when the two ex-U&N locomotives were acquired by the Columbia & Puget Sound. U&N 23 became C&PS 3:2, and 37 became C&PS 4:2. The Columbia & Puget Sound was standard gauged in 1897, and again the locomotives were up for sale.

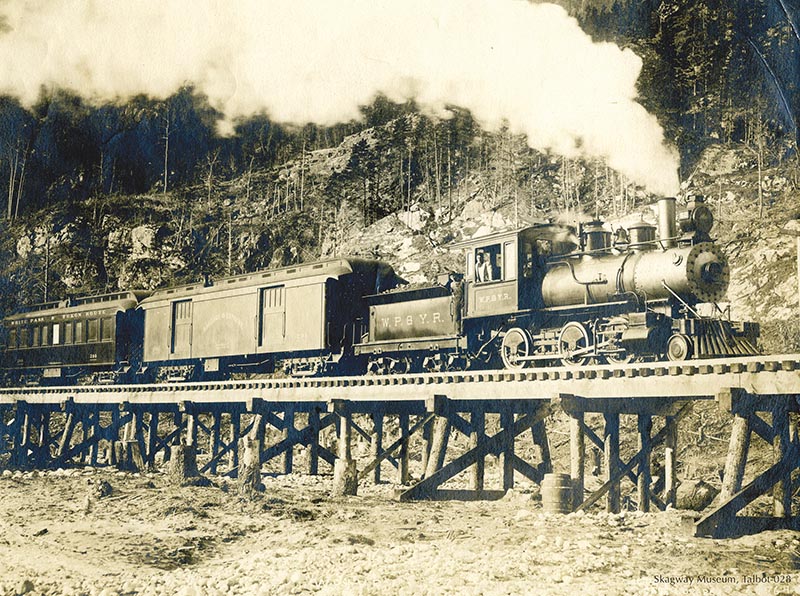

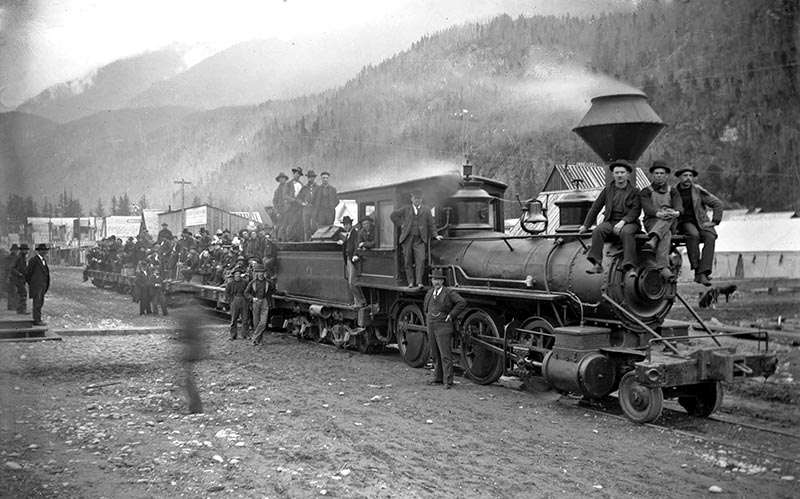

ABOVE: WP&YR 2 prepares to haul the very first train, full of enthusiastic townsfolk, four miles north out of Skagway on July 21, 1898. Number 2 was the first locomotive in the Alaska Territory when she arrived in Skagway on July 20, 1898. This first excursion train also made No. 2 the first locomotive to operate so far north. —H.C. Barley photo, Skagway Museum Dedman Collection

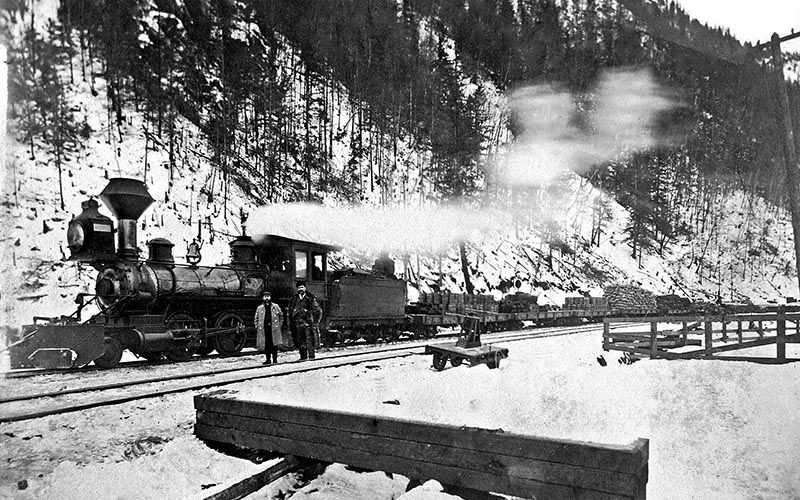

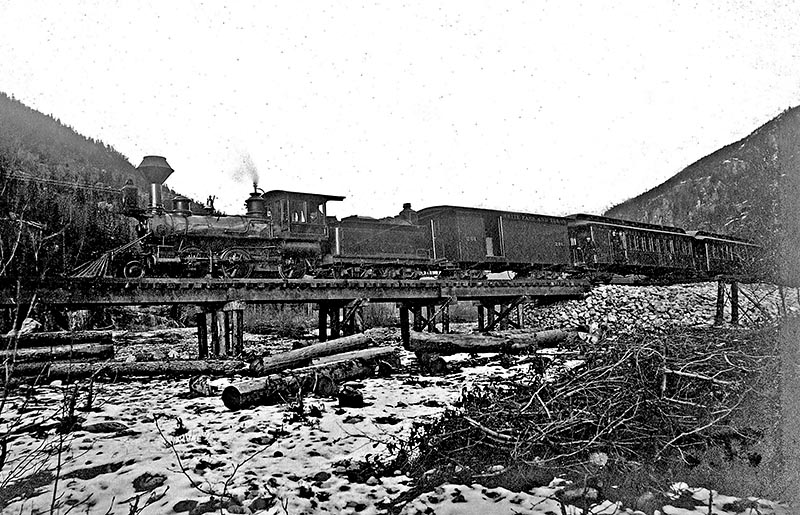

Due to the Klondike gold rush, which was already in full swing, construction of the White Pass & Yukon Route began on May 28, 1898. On July 20, 1898 the first locomotive in the Alaska territory arrived and was unloaded from a barge in Skagway, Alaska. The next day, the same locomotive; the White Pass & Yukon Route’s No. 2, the ex-U&N 37, ex-C&PS 4, steamed north out of Skagway pulling a few flatcars full of exuberant townsfolk over four miles up grade. Number 2 was also the first locomotive to operate so far north. I am unclear as to whether 1 arrived on the same barge, or days or even weeks later, as the White Pass purchased a total of five locomotives from the Columbia & Puget Sound in 1898. Construction continued in the harsh conditions through the winters of 1898 and 1899 with these locomotives hauling construction materials and excursion trains. Two new boilers for the two aging Brooks engines arrived onboard the AL-KI, on September 9, 1899.

Locomotives 1 and 2 were rebuilt in 1900 with these new boilers accompanied by new cylinders. New, 46-inch diameter steel boilers replaced the aging 44-inch diameter wrought iron, wagon-top boilers. The fireboxes were raised and widened, and the new cylinders (141/2- x 18-inches) were installed to fit the larger and higher boilers. The boiler pressure was increased from 135psi to 185psi, (although, a folio diagram from 1908 gives a boiler pressure of only 160psi). Along with the rebuilding in 1900, the White Pass set about renumbering its fleet of locomotives, 1 became 51, and 2 became 52. The new boilers and cylinders must have been well worth the money and effort as both of the moguls out lasted their ex-C&PSRR sisters on the White Pass. Number 51 stayed on the White Pass until 1920, and 52 until 1931.

ABOVE: WP&YR No. 1 with a train load of construction materials ready to head north, circa 1898. Number 1 can be identified by the location of the injectors on the side of the boiler. No. 2’s injectors were farther forward. Of course this changed when the locomotives were rebuilt with steel boilers in 1900. Note the flanger actuator mounted on the side of the smokebox. —Bruce Pryor collection

Another gold strike occurred in July 1898 near Atlin, B.C. To ease access to the gold fields, the 2½-mile-long Atlin Short Line & Navigation Co. wooden tramway opened in June 1899 across the isthmus near Taku Arm to Scocia Bay on Atlin Lake. In June 1900, the White Pass & Yukon Route bought out the assets and completed the line, now known as the Taku Tram. With no way of turning the locomotives, they had to run forward from Taku to Scotia Bay and backwards for the return.

This short line had a maximum grade of 7 percent and a single 12-ton, open passenger car. When the Tram’s first locomotive was taken out of service in 1920, the White Pass brought in old locomotive 51. In 1931, 51 blew out a chunk of her main steam pipe, and they replaced her with 52. Photos show that only the locomotives were swapped, 52 using 51’s tender while on the Taku Tram. The White Pass repaired 51 and used her until retirement in 1941. Number 52 was the motive power on the Taku Tram until 1936 when she was stored in Atlin; replaced by a Westminster Iron Works gasoline powered locomotive.

Number 51 was outside the Whitehorse, Y.T., engine house when the engine house burned down in December 1943, destroying numbers 10 and 14, two ex-East Tennessee & Western North Carolina ten-wheelers. She evidently escaped with little or no damage and was displayed in 1958 at the MacBride Museum in Whitehorse, and remains there today.

ABOVE: The first passenger cars arrived in Skagway on September 10, 1898. Here No. 1 pulls a passenger train across the Skagway River sometime after their arrival. —H.C. Barley photo, Bruce Pryor collection

A volunteer group called Project 52 retrieved 52 from Atlin in 1964 using a Caterpillar tractor and sled to get the engine across the frozen surface of Atlin Lake, and then a low-boy truck to get her back to Whitehorse. After a thorough greasing of the bearings, the 80 year old engine was brought back to Skagway behind White Pass Diesel locomotive 92 and a volunteer crew. Number 52 was stored next to the Skagway roundhouse when the roundhouse burned on October 15, 1969. Fortunately, only the tender’s deck and frame were damaged. She was put on display at the United Transportation Union Hall in Skagway in 1971. In 2000, 52 was taken to the WP&Y shops for asbestos removal, where the shop crews removed the lagging from her boiler. Number 52 was cosmetically restored in 2014 and placed on display near the Skagway depot, where she can be seen today. In 2019, Chuck Morse began restoration on the tender deck and frame.

It is truly amazing that these two locomotives each gave over 45 years of service, and they both survive to this day — over 140 years since they rolled off of the Brooks Locomotive Works assembly floor. Oh, but the stories these locomotives could tell if they could only talk, stories of the sourdoughs and the Gold Rush, stories of the construction of “The Scenic Railway of the World,” stories of the battle to construct the 1500-mile Alcan Highway, stories of almost unimaginable cold, and so many more stories.

I would like to thank Bruce Pryor, Robert Hilton, John Stutz, and Boerries Burkhardt, for their assistance and generosity with photos and information. In the next issue, I will investigate an early D&RG connection with the White Pass accompanied by another fantastic drawing by David Fletcher.